Content warning: discussion of trauma and sexual assault

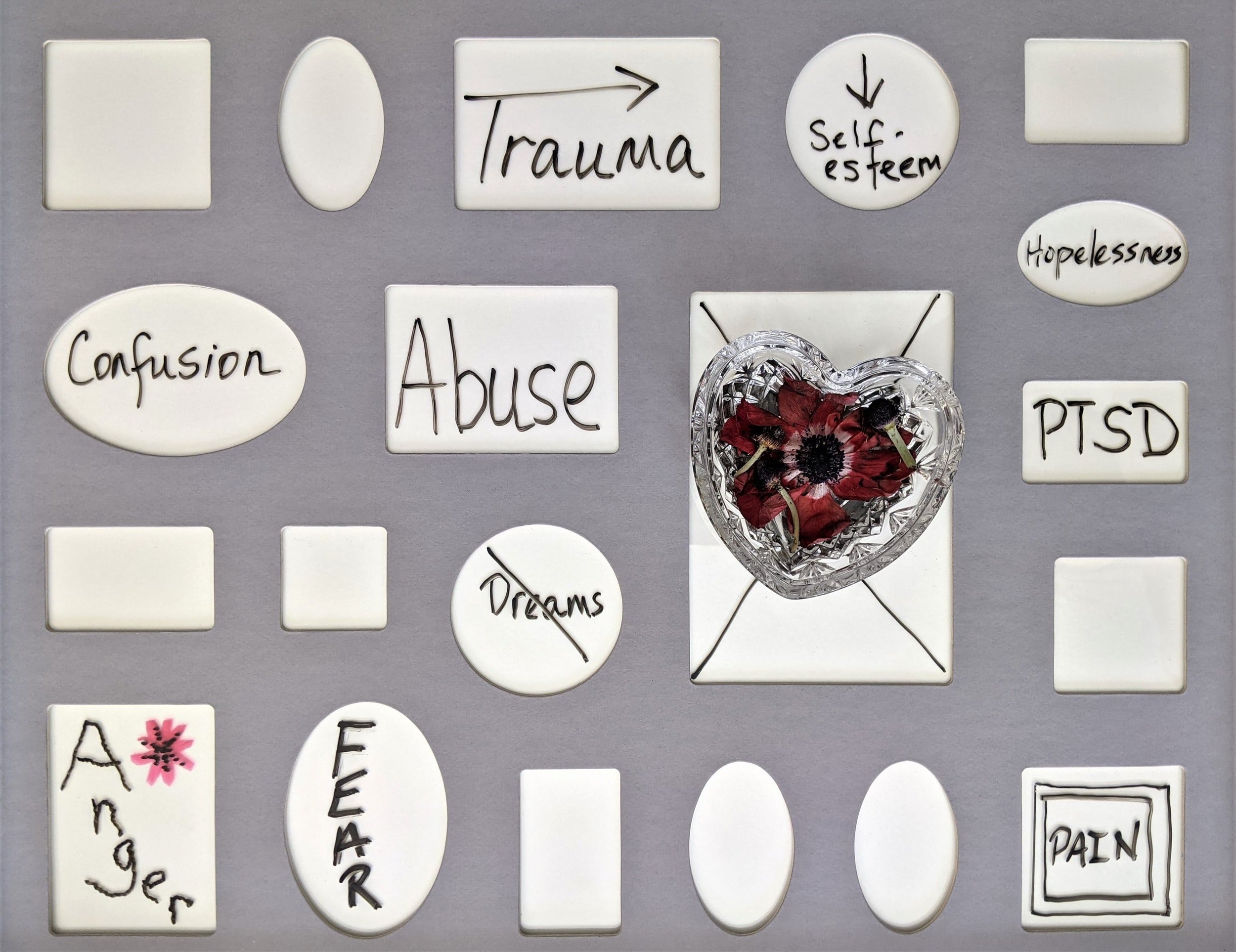

Sexual trauma is one of the most harrowing experiences someone can go through and unfortunately, it’s far too common. Sexual trauma can be caused by any kind of non-consensual sexual experience; including rape, sexual assault, sexual harassment, and childhood molestation. Given that trauma is subjective, it is up to the individual to determine how to define their experience. On average, there are 450,000+ survivors of rape and sexual assault every year in the United States, a number which is likely underreported. Survivors of sexual trauma frequently struggle with PTSD and are more likely to abuse drugs and alcohol to cope. Experiencing sexual trauma has the potential to upend someone’s entire life, not least of all their sex life. Trauma responses can range from sex repulsion to hyper-sexuality. There is no one timeline or coping strategy that will work for every survivor of sexual assault so the most important part is to respect one’s own boundaries and to move at a pace that feels comfortable. There’s no obligation to return to consensual sex but for those who want that, healing is possible, even if it is sometimes challenging.

Common obstacles to resuming consensual intimacy may include negative body image, flashbacks, and PTSD. If it’s accessible to you, work with a trauma informed therapist to facilitate your healing process. Embrace Sexual Wellness offers therapy to address sexual trauma concerns and you can learn more about our services here. In the meanwhile, the following tips and resources can assist your healing process.

General Tips

Identify your specific triggers and boundaries to understand what your healing process should work to address

Move at your own pace

Explore intimacy solo before partnered

Test out different coping mechanisms for trauma healing such as talk therapy, mindfulness, and medication

Reassociate intimacy, touch, and sensuality with positive connotations

When returning to partnered intimacy, be in constant communication

Body Image

If your body image has been affected by sexual trauma, it may put you at risk for self-harm or disregard for your own safety so it is vital to address as soon as possible

Surround yourself online and in real life with a diverse community of body positive or body neutral people, especially on social media

Understand that you deserve peace and to feel worthy. You deserve self-compassion

Resources

The Body is Not an Apology by Sonya Renee Taylor

Sex for One: The Joy of Self-Loving by Betty Dodson

Flashbacks/PTSD

Test out different coping strategies for flashbacks to see what works for you; if you have access to a mental health professional, develop coping strategies in conjunction with them

Try grounding strategies

Talk it out

Remember that healing is not linear and there is no wrong way to heal

Seek out therapy. If it’s not accessible to you, check out our mental health resource roundup

Avoid drugs and alcohol

Acknowledge small victories

Resources

Reintroducing Intimacy

Start out by working up to solo intimacy. This could be a warm bath, taking sensual photos, reading erotica, and/or masturbation, along with anything else you might want to try

Determine your triggers and boundaries and communicate them to partner(s) when applicable

Have an emergency plan in case you become triggered in everyday life or during sex to calm down and prevent from spiraling

What feels pleasurable might change after sexual trauma. Remain flexible in your thinking about what pleasurable intimacy looks like

When attempting partnered intimacy, constantly communicate with your partner(s) about how you feel, what feels good, boundaries, and whether you want to keep going

Resources

Reclaiming Sexuality

Masturbation can aid in reclaiming a sense of control and ability to experience sexual pleasure

Both hypo- and hypersexuality are normative post-trauma responses

Read articles and books to guide you through reclaiming your sexuality. Good book options include

The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk

Dear Sister: Letters from Survivors of Sexual Violence edited by Lisa Factora-Borchers

The Rape Recover Handbook: Step by Step Help for Survivors of Sexual Assault by Aphrodite T. Matsakis

The Sexual Healing Journey by Wendy Maltz

Healing Sex: A Mind-Body Approach to Healing Sexual Trauma by Staci Haines

Talk about shame, obstacles, concerns, and intimacy through with a consenting friend or, ideally, a mental health professional

Be patient and kind to yourself

Resources

Regardless of your experience or post-trauma response, you deserve to heal, reclaim your sexuality, and enjoy sex again (if you enjoyed sex pre-trauma). Your experience is valid and please give yourself grace as you navigate the complex feelings associated with healing trauma. Build your support network, read up on healing strategies, and be patient. If you’ve tried healing on your own and you need more support, contact us for trauma-informed therapy.